Vintage Truck Editor Steals Bigfoot!

/Preface

How is it that the editor of Vintage Truck magazine got to drive one of the most famous Ford pickup trucks in the world? I’m glad you asked.

In November 2003, I was writing a 20-year history of the Saleen Mustang and having a rough time with it. My wife Heather and I had chosen to self-publish the massive work, which proved to be more stressful than I imagined at the onset. Schedules were ripped apart like single-ply toilet paper in a twister, and the projected cost tripled as the book ballooned to 430 pages. It was clear to those around me I would be a burned-out shell by the time the book went to press.

What I needed was a road trip of truly epic scope!

Ignoring the strobe-like nervous tic of my right eye and the volcano in my stomach, I consulted a road atlas, surfed the Internet, and put my brain on high alert for any idea that could turn into a paycheck. The result was a concept in which I would cover the spectrum of advanced and high-performance driving schools available to the public, starting with the basics and moving up to faster and fancier offerings.

Because I am a driving fool, there would be no air travel involved. Like Chevy Chase’s character in National Lampoon’s Vacation, I would ignore the convenience (if you want to call it that) of jets and cover every mile on pneumatic rubber—stopping to visit the world’s largest ball of twine and making new friends along the way. Because I love all manner of cars, trucks, and motorcycles, I set a goal of driving a different vehicle on every trip, a twist that would further personalize and individualize the experiences for me.

I phoned my editor at Krause Publications, who enthusiastically managed a lightning-fast 24-hour approval based on the same description I’ve just shared with you.

During the next 12 months, I attended 11 driving schools in 10 different states, covered 16,613 miles in an array of borrowed, rented, and personal transportation, and consumed around a million calories, ranging from quick-and-easy road food (Krystal Hamburgers are still the best!) to fit-for-a-king meals (the dining room at the Biltmore Estate).

As expected, I became more relaxed with each trip, coasting along America’s two-lane highways, listening to local radio stations, and throwing myself into each school’s driving exercises. For most of these journeys, I was accompanied by a different friend who acted as co-photographer and all-around helper.

Unfortunately, my Preface does not have a happy ending. I turned in the 77,000-word manuscript and hundreds of digital photos, cashed my check, and waited for printed copies of Drive It Like You Stole It! to arrive. What came instead was an email letting me know the publisher’s new owners were pulling 50 titles from the 2005 catalog, and my book had been chopped. (To their credit, the Krause people returned all rights to the material, but I was unable to interest another publisher in the manuscript.)

Now, in 2026, after more than 20 years, I have dusted off the manuscript and am sharing with Vintage Truck magazine readers one of the most exciting days of my career.

Yes, this is about “The Day I Stole Bigfoot!”

Enjoy.

Realize that the following chapter was written in 2004-05, and no attempt has been made to update information on facts such as how many championships Bigfoot has won.

Monster

Take this Job and Love It!

By Brad Bowling—Editor, Vintage Truck

When I stood beside Bigfoot for the first time in my life, the tops of his signature tires were level with my forehead, and the door handles—had there been any such hardware on the all-fiberglass body—would have been a few inches beyond my best attempt to touch them.

Is this how a prehistoric mammal saw Tyrannosaurus rex before becoming a snack? Overwhelmed by the size of the creature before it? Too awed to act in its own defense?

No, I assured myself, I’m here to tame this beast. Under my control, its prey would be the four luckless sedans huddled together at the center of the Hazelwood, Missouri, parking lot, windows pre-shattered to cut down on flying glass.

My father, James “Pack” Forbus, and I were taking a tour of Bigfoot 4X4’s headquarters on the northwestern edge of St. Louis to learn more about the original monster truck before I climbed in for a driving lesson. We had ridden up to Hazelwood from Mississippi the day before, swapping out between his 1997 Harley-Davidson Heritage motorcycle and the family’s Chrysler LHS that served as our equipment and luggage hauler. I had put together a 450-mile route of old country highways through Tennessee, Kentucky, and Illinois, so seat time was relaxing and scenic for both of us.

Video was shot by: Bob "Bigfoot" Chandler

The man behind the foot

In an office surrounded by mementos of the entertainment/sports segment he created, Bigfoot 4X4 CEO Bob Chandler was the very picture of Midwestern modesty when we sat down to talk.

There were images on the wall of his Bigfoot Blue Ford trucks leaping and crushing unrecognizable metal pulp in dozens of countries while thousands of paying spectators looked on. A ball cap given to him by a producer of That’s Incredible! was but a hint of the television coverage Chandler’s baby has received over the last quarter of a century. The silver screen has been equally attentive, as an original movie poster for Take This Job and Shove It! attests. Dozens of diecast models have been created to honor this truck that launched a thousand imitators; a few of the mini monsters lurked on the shelves of Chandler’s packed bookcase and atop every table in the room.

Having such résumé material would surely turn most folks into raving egomaniacs who start each sentence with “I was the first to...” or “I’ve done the most to...” but not so Chandler, to whose imagination and hard work a generation of extreme sports enthusiasts will forever owe a debt of gratitude.

Chandler admits the idea for Bigfoot originated from purely practical transportation needs.

“I was always a Ford person,” he remembered. “I bought a ’67 4X4 pickup and installed a camper shell so my wife Marilyn and I could drive to Alaska for contracting work. That was a primitive rig that sat really high in the air to give clearance for all the add-on 4X4 equipment, but it did well for us on the Alaska-Canada Highway.

“I think the seeds for Bigfoot were sown on that trip when I replaced the stock tires with bigger ones after the AlCan destroyed the originals. At that time, if you wanted any 4X4 accessories such as a winch or suspension parts, you just about had to make them yourself because there was no aftermarket like today.”

The first Bigfoot started life as Chandler’s stock ’74 Ford F-250 pickup, whose abilities and popularity quickly grew while Midwest Four Wheel Drive Center (at that point consisting of Bob, Marilyn, and neighbor Jim Kramer) applied a constantly evolving list of equipment; a 460ci V-8, 18x19.5 Super Single tires, Dana 70 1-ton axles, frame reinforcements, stronger springs, stiffer shocks, and, in 1978, four-wheel steering, to name a few. Bigfoot 1 would eventually be fitted with 18 different combinations of wheels and tires as Midwest searched for the perfect setup. Chandler and Kramer’s mechanical innovations and instinctive marketing skills kept their loud and nasty mud racer at the forefront of the monster truck industry that was just beginning to wake up.

In its early years, Bigfoot, named for Chandler’s habit of breaking parts in competition, served Midwest as a show vehicle, competition mud racer, and rolling advertisement. The street-legal truck even acted as a tow rig on several occasions, often wearing a fiberglass camper shell to protect tools and other cargo. Midwest forever cemented its reputation as king of the 4X4 hill when Chandler drove the beast in the 1980 feature film Take This Job & Shove It!, a role that bent the truck’s frame, ruined eight shock absorbers, destroyed two tires, and required Chandler to shave his 10-year beard to double for actor Tim Thomerson.

In 1981, without a clue of its true significance, Chandler made a giant leap for truck kind by driving his heavily modified Ford over a pair of cars in a Missouri cornfield. Having run over enough large obstacles in mud races, Chandler suspected Bigfoot’s ever-growing tires, super-strong frame and 8,000-plus pound curb weight would easily climb and crush a junked car. So eager were Chandler and Kramer to conduct this experiment that they accidentally left a toolbox in the open bed!

That car crush soon became a staple for every Bigfoot and monster truck performance that followed.

Competing in any field of motorsports requires a tremendous amount of sponsor money, which is why Ford Motor Co.’s early interest in and support of Chandler’s operation was instrumental in growing the new industry.

“I met Edsel Ford II at a SEMA show about 15 years ago, where Bigfoot was on display. Later that year, he came to an event at the Pontiac [Mich.] Silverdome and rode in the truck with me. That was in the days when we just drove over the cars and crushed them without any jumping. He told people at Ford about Bigfoot and the enthusiasm it generated for the truck line; we’ve been sponsored by them ever since.”

The machinery and driving techniques evolved rapidly in the early part of Bigfoot’s career—usually as part of a carefully laid plan, but sometimes by sheer accident.

“Since we were inventing and refining the monster truck concept as we went along, there were surprises and discoveries at every step. We were filming a commercial in 1982 for Warn winches, and the company wanted us to back Bigfoot into the water so it could be towed out using one of its products. The back end lifted completely off the floor of the lake and started floating, which started us thinking maybe there was enough buoyancy to keep Bigfoot above the water line. It worked, and we got a lot of exposure for the truck with that stunt.

“Driving in the water looks neat but takes a tremendous amount of cleanup and maintenance back in the shop. We haven’t done it in a while—partly because the early trucks were more stable in the water, partly because there hasn’t been much demand for that trick lately.”

In 1982, Bigfoot 1 was joined by Bigfoot 2, which itself became a standard-bearer for the industry by wearing the first 66x43x25-inch heavy-duty off-road machinery Firestone tires. A year later, Bigfoot 2 begat Bigfoot 3 (first to use dual 66-inchers on each corner), which begat Bigfoot 4 (first to perform a wheelie while pulling a sled in competition).

With a mandate from the public to make Bigfoot bigger and more powerful, it was inevitable Chandler and crew would install a set of the largest tires ever produced.

“When I was in Seattle many years ago, I saw a set of tires Firestone made for the military’s Alaskan land train in the 1950s. The land train was a gigantic machine designed to move men and equipment over the tundra on these 10-foot-high tires; sometimes they were set up in pairs of duals on each axle. The owner of the salvage yard wanted $30,000 each for the tires and didn’t budge when I went back the next year and asked again. Somehow, when Jim Kramer took a truck to Washington a year later and stopped by, the guy sold us four of them for $1,000 apiece and another set of four for $700 each.

“We experimented by installing them on Bigfoots 1, 2, and 4 for different events, then built Bigfoot 5 specifically to handle them. Each wheel and tire combination weighs about 2,400 pounds.”

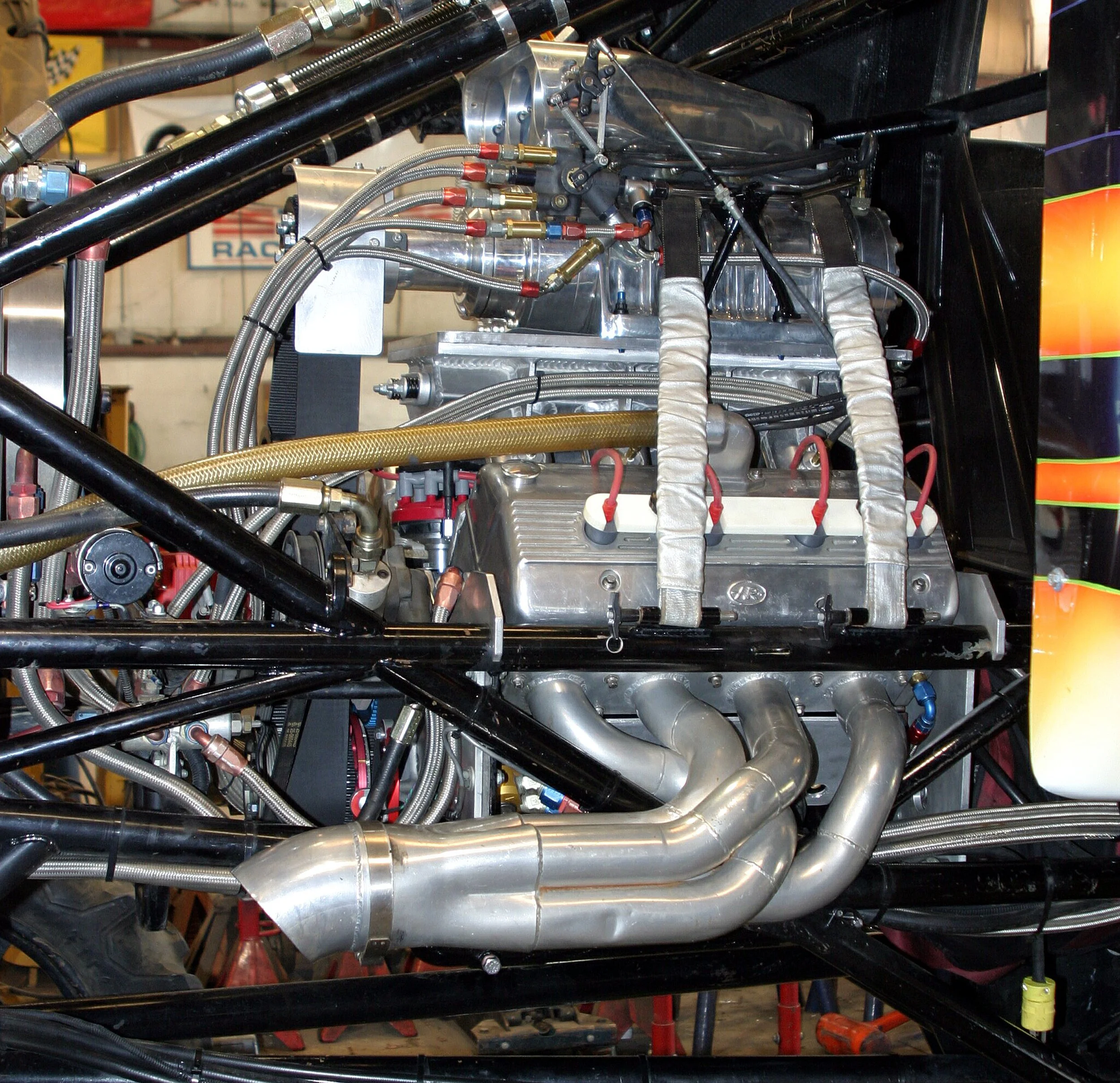

Every iteration of Chandler’s truck lays claim to a “first” or “best,” but the most significant leap in the line’s evolution came when Bigfoot 8 was introduced on a chassis built entirely of tubular steel. The racecar-like skeleton did not trim overall vehicle weight, but its strength and compactness gave the trucks an agility never before seen in an 11,000-pound vehicle. Bigfoot’s performance with the new frame (and an experimental cantilever suspension system, later discarded) put it light years ahead of the competition. Handling was improved again when Bigfoot 10 debuted with its big-block Ford V-8 situated behind and below the driver compartment.

“When I drove Bigfoot 1 over its first set of cars, I had no idea how much potential the trucks had for jumping. I was certain that all four wheels leaving the ground at once would break the thing in half—and that was probably true on those early models. That all changed when we built Bigfoot 8 in 1989. Losing the truck frame made all the difference in the world, and suddenly our drivers were able to jump 20, 40 ... 60 feet without damaging the trucks or themselves.

“In 1999, Dan Runte launched Bigfoot 14 off a 10-foot ramp in Nashville and cleared the wingspan of a Boeing 727 jet. He traveled 202 feet and landed in the Guinness Book of World Records. It was an amazing stunt, especially when you consider Bigfoot weighs around five tons, and we spent a lot of time practicing for it. We wanted to make sure nothing could go wrong.”

Bigfoot’s family tree is dotted with several relatives including Ms. Bigfoot (a Ranger pickup with 429ci V-8 power), the Bigfoot Shuttle (an Aerostar minivan motivated by a stock V-6 and nitrous oxide), and the bizarre Bigfoot Fastrax (a tank-treaded M84 military personnel carrier sporting two 460ci Ford V-8s).

In the three decades since its birth, the emphasis of the monster truck world, influenced largely by the Bigfoot flagship, has moved from mud racing to sled pulling to car crushing and, ultimately, to obstacle course racing. Bigfoot drivers have captured 13 championships as of 2003—12 of those in consecutive years! The phenomenon has spread to dozens of countries around the world, and the name “Bigfoot” is the most widely recognized of any custom vehicle ever.

(The story will continue after the photographs.)

Driving Bigfoot

In 2003, Bigfoot 4X4 announced a monster truck driving school for the public, but demands on the crew’s time and other concerns caused the company to withdraw the offer. Today, the only people who get to strap on a 5-ton Bigfoot and crush cars with supervised instruction are up-and-coming exhibition and competition drivers, the occasional Ford bigwig, motivated celebrities, and very lucky automotive writers who ask politely.

Obviously, I fall into that latter category.

My Bigfoot class consisted of three other aspiring monster truck drivers. Rick Long had been with the company for two years, having put his hydraulic and welding skills to good use in the shop and on the road. Twenty-two-year-old Chris Ludwig was an all-around crew guy for the Bigfoot drivers. Both men were being groomed for competition.

The final member of our quartet was 29-year-old Bobby Chandler, Bob’s son, who has been taking an active role in Bigfoot’s business side since college. Contrary to what you might assume, Bobby had never used his father’s toy to crush parked cars or show off for the girls despite obvious connections, so it would be a special day for both of us.

In the parking lot that doubles as a test track, I met our instructor for the day, Eric Meagher. Meagher was an appropriate teacher, having driven Bigfoot to back-to-back championships in 1997 and 1998—a feat he pulled off in only his third year of competing.

Meagher and I were talking next to the neat corral of junk cars when we were interrupted by the sound of more than 1,000 horsepower hitting the ground. Bigfoot 11 was moving in our direction from behind the shop at a stately parade speed.

Because he already had some experience driving the truck onto transporters and on flat surfaces, Long was told to suit up and take the first set of runs. Once belted into place, Long took one slow practice lap around the parking lot and pulled the truck’s front tires against the rear bumpers of a Chrysler LeBaron and Honda Accord. With one stab on the throttle and an angry cough from the V-8’s straight exhaust, Bigfoot lifted its front wheels and parked them on the cars’ trunks. Although the sheetmetal did not crush noticeably on that first contact, it was clear the cars’ suspension pieces would no longer do anybody any good.

Long’s move had just been a warm-up, a step to create a more suitable ramp out of the Chrysler and Honda. After backing up and getting all four of Bigfoot’s tires on the flat ground, Long began inching forward as if trying to not frighten his victims before pouncing. When Long nailed the accelerator, Bigfoot reared up like that T. rex and drove all four tires across roofs, trunks, and hoods before returning to pavement on the other side.

It was a very smooth first try, and I wondered if it had been as easy to pull off as it looked. After returning to his launch position, Long put to rest my concern that I might have a career in monster truck driving when he got air under all four wheels and came down hard on the junk cars. On his third run, he executed one of Bigfoot’s famous maneuvers, sailing through space with the front wheels riding higher than the rears, making it even clearer to me that I would not be joining the circuit ahead of my fellow students.

My turn

When Long parked Bigfoot and killed the engine, several crew members tidied up the target cars for my round, and I slipped into a new, flame-covered, two-piece fire suit whose stiff protective layers made me walk around like an Emperor Penguin after hip surgery. The suit I borrowed was made for a larger person; someone commented that Dan Runte and I were about the same size.

For the sake of convenience, Meagher gave me Monster Truck 101 instruction while we stood on the pavement before installing me in the cockpit.

He addressed the issue of vehicle stability first.

“For what you’re about to do,” he assured me, “there’s not much that can go wrong. It’s like driving a really tall car over a speed bump.

“It may feel like you are up high, but the truck’s center of gravity is very low, so you can’t tip it over at the speed you’ll be going. Once you get on top of the cars, keep going and drive off the other side.”

He gave me the option of switching on Bigfoot’s rear-wheel steering system but suggested my time in the truck would be better spent if I didn’t have to worry about superfluous controls. Remembering Meagher’s two monster truck championships, I decided to let him do all the thinking and agreed to get by on front-steer alone. The other, more experienced students were using all four for steering, but only to get around the parking lot quicker; the system would be turned off while in full crush mode.

Meagher showed me the device that would prevent my going on an unintended rampage of destruction and mayhem—a walkie-talkie-like box whose purpose is to interrupt the truck’s ignition in case the driver passes out from a hard landing or has mechanical trouble that causes a stuck throttle. The monster truck industry has used this fail-safe mechanism in competition and exhibition events since it became evident an out-of-control behemoth could wreak much damage. Knowing when to operate the kill switch is not as easy as it might seem, according to Meagher, who says drivers often use the truck’s power to pull out of a bad situation. Shutting them down too early can result in the kind of accident the driver is trying to avoid.

With instructions firmly implanted, I approached Bigfoot 11 and marveled again at its intimidating mass. Introduced to the monster truck world in 1992, number 11 was the second of the line to have its engine behind and below the driver. Paradoxically, although the body sits slightly lower on the frame than others of its series, it has the greatest suspension travel of them all, with a range of 32 inches top to bottom. Like Meagher, number 11 is also a former champion, having secured Bigfoot’s fourth season victory in 1994. A year later, driver Eric Tack set a world record by flying the truck 117 feet through the air; in 1999, it set a wheelie record of more than 217 feet with Dave Harkey in the cockpit.

Reaching the driver’s seat from ground level requires ducking under the fiberglass body side panel and climbing the tube-frame chassis like a jungle gym. My girth was considerably greater than I normally carry on my 135-pound frame because of the Sta-Puft Marshmallow Man fire suit, and I took care during my climb not to catch it on anything. Once in the driver’s seat, I looked through the plastic windshield across Bigfoot’s high hood and felt like the captain of my very own treehouse.

By the time Bigfoot 11 debuted at the 1992 SEMA show in Las Vegas, monster trucks no longer had any parts in common with their lower, more comfortable pickup cousins; this built-from-scratch philosophy extended to the interior, which is as Spartan as any single-purpose racer. Gauges sit well below eye level—no speedometer, of course—and no attempt was made to hide the wires that connect to a small panel of switches. Industrial-strength accelerator and brake pedals are large and flat, so drivers keep control of Bigfoot, even when things get crazy. The shifter is a drag-style unit that allows manual gear changes.

In its early days, Bigfoot had a stock Ford pickup bench seat and Chandler and Kramer would crush cars while hanging their heads out of the driver’s window for a better view. Their helmets were open-face models that left chins and noses unprotected in the event of a heavy landing. Bigfoot 11 features a single padded racing seat directly in the center of the cabin, and I was wearing my Snell 2000-rated full-face helmet for protection.

The firewall—well, what would be a firewall on an ordinary pickup—is made mostly of clear Plexiglas that allows the driver to see some ground just ahead of the front tires as well as the 22-gallon fuel cell full of methanol.

Meagher followed through the metal maze and prepped me for takeoff, starting with the five-point safety belts, sternum strap, and neck brace. Once I was all but immobile, he told me to take a few slow laps in the parking lot to learn how the beast handled, then return to my start point for more instructions

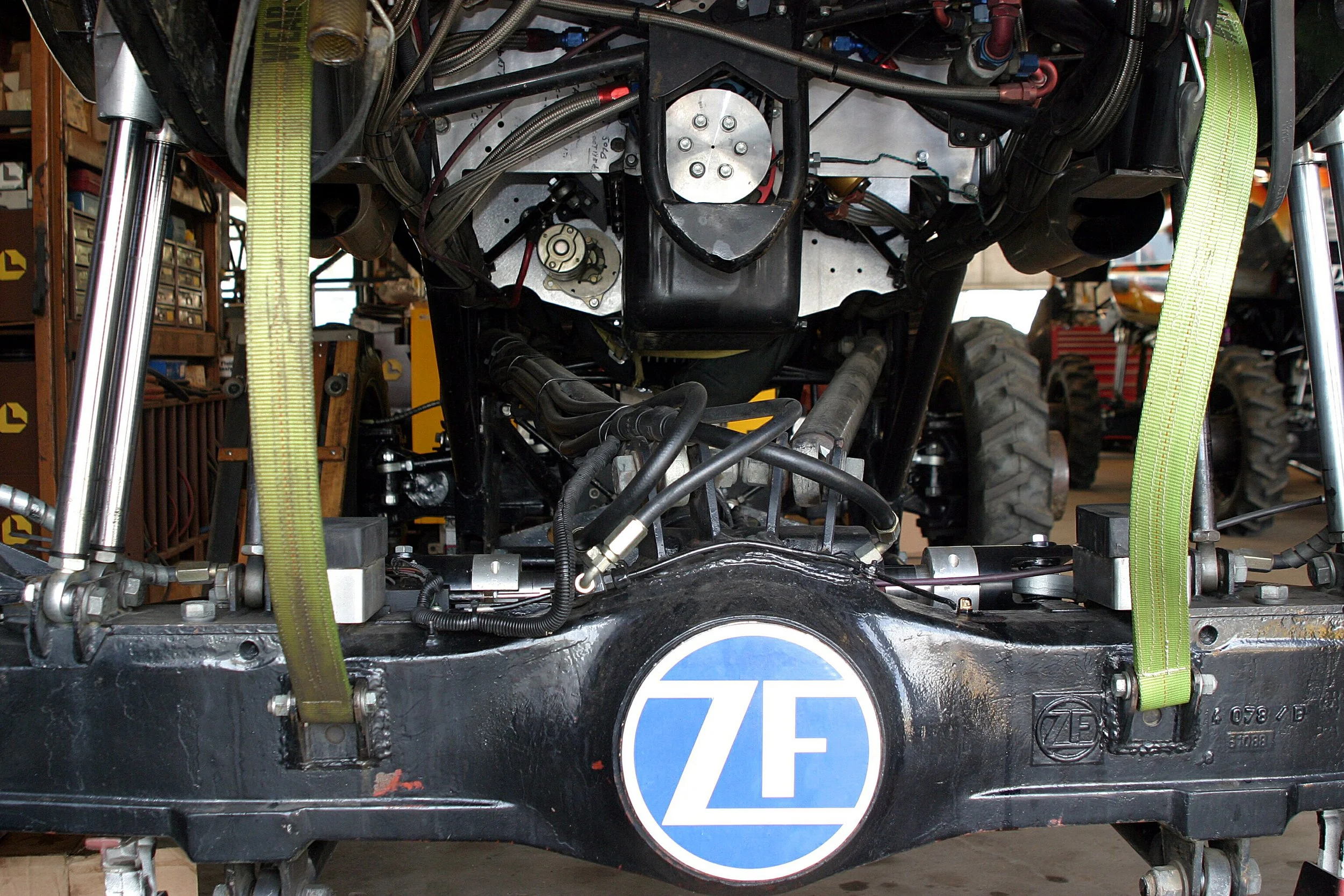

Meagher flipped a switch, pulled a lever or two and pushed a button, causing 572 cubic inches of big-block Ford V-8 to come to life. When competing, that size is the upper limit for engines, but an 871 supercharger with 10 percent overdrive pulleys pushes horsepower to the 1,400 range. All that rage runs through the 3-speed automatic transmission into gear-drive transfer cases and splits to the heavy-duty ZF axles. Planetary gear reduction in the hubs allows the use of smaller axles. The sound is not unlike that of a NASCAR stocker—yes, I’ve driven a few of those, also—and the short exhaust pipes point to the ground.

I lifted the shifter handle, ratcheted down to second gear and cautiously released the brake. At idle, Bigfoot is generating enough torque to move itself forward between five and 10 miles per hour. The throttle was very stiff, like a reluctant on/off switch, and as I stabbed it with my right foot, the truck would jump forward, rocking my cockpit like a hobby horse. I made three circuits of the parking lot, each pass requiring a gear shift to Reverse to maneuver the big truck through a three-point turn in the grass.

I put Bigfoot in Park and signaled Meagher it was safe for him to board. He joined me on top of the jungle gym and ran through a brief engine shutdown before we could talk again. Since I was a newbie, he wanted to know if I had any questions before turning me loose, but I assured him I had it under control.

Under power again, I approached the junk cars, which I could no longer see over the hood once I got to within 20 or so feet. The clear firewall gave me the briefest glimpse of my target, at which point I engaged the throttle to give Bigfoot some climbing power. The bark of the engine coincided with the feeling I had just hit a curb, and I managed to get two feet of air under the front tires before they crashed down on the Honda and Chrysler. With only mild throttle applied, I drove across the four cars and felt a soft drop as the front tires fell to the pavement, followed a second later by the rears. My first monster truck car crush had gone as smoothly as if I had just pulled into a McDonald’s parking lot.

After a three-point turn, I set up for another run. My use of the throttle leading into my second attempt did not produce a spectacular launch but did provide enough momentum to easily mount the flattened cars. My third and last run was a repeat of the second, and I found I was getting very comfortable with the idea of running over large obstacles in a monster truck. Unfortunately, my slow learning curve would have to end there, as two other students were eager to burn some gas.

After parking and shutting down the truck, I climbed back down to the pavement and was greeted by Chandler, who had videotaped my several attempts to achieve monster truck stardom.

While he didn’t instantly offer me a job as a Bigfoot driver, he was very positive in his critique.

“You did about what I did in ’81 when I ran over those first cars. I didn’t do anything fancy, either.”

Coming from Chandler, it was high praise. I asked him at what point in his history did he realize he was giving birth to a cultural phenomenon.

“It was never my intention to do what we’ve done,” he admitted. “I’m not that smart of a person. Bigfoot happened because I had a truck I took to off-road events and it broke a lot because of the abuse. We put bigger tires on it for better traction, which meant the engine bogged down. When we put in a more powerful engine, we tore up transmissions and snapped axles. Frames bent.

“The idea was to keep throwing money and parts at the project until we found that perfect combination. I’ve been fortunate to have some great people working with me, especially my wife Marilyn, who has the business instinct. The reaction we’ve gotten from fans worldwide has been motivating us for nearly 30 years, and we’ll keep doing it as long as it makes people happy.”

(The story will continue after the photographs.)

SIDEBAR:

And what did we learn?

Bigfoot was unlike anything I’ve driven before. Forget everything you know about weight transfer, oversteer, contact patches, and any other left-brain concepts. Today’s monster truck is just a set of wings shy of being an STOL aircraft. Bigfoot doesn’t go OUT as much as it goes UP, which means a track can take up less space than half of a football field and still provide runoff room.

I must admit I did not become proficient at monster truck handling during my brief time at the wheel, but I suspect finesse with the throttle is the key to bouncing something the size of a single-family dwelling 20 feet into the air.

If you can't find Vintage Truck on a newsstand near you, call 800-767-5828 or visit our Gift Shop to order current or back issues. To subscribe, call 888-760-8108 or click here.